Olen tässä viime kuukausina pohtinut miltä tuntuisi jos ruuasta olisi pulaa? Miten helppoa olisi sopeutua siihen, että tiettyjä ruokatarpeita voisi ostaa vain hyvin rajattuja määriä, jos ollenkaan? Saisimmeko nälän karkotettua vai menisimmekö nukkumaan kurnivin vatsoin? Herkkuja ei juuri olisi tarjolla ja pikkunälän yllättäessä kaapissa ei ehkä olisikaan hapankorppua tai voileipäkeksejä. Pitäisi pärjätä pienemmillä ruoka-annoksilla, korvaavilla ruoka-aineilla ja lisätä marjoja, sieniä ja itse kasvatettuja vihanneksia ruokavalioon.

Suomen joutuessa mukaan toiseen maailmansotaan, ensimmäiseksi kortille menivät kahvi ja sokeri, lokakuussa -39. Myöhemmin ostokortille joutuivat mm. viljat ja leipä, tee, kuivahedelmät, maito, juusto ja voi, kananmunat, liha ja pahimman pulan aikana myös peruna. Muita ostokortilla saatavia tuotteita olivat vaatteet, jalkineet ja saippua. Pulaa oli kaikesta muustakin, kuten lääkkeistä, polttoaineesta ja käyttöesineistä. Ostokortteja oli käytetty myös ensimmäisen maailmansodan aikana. Suomi ei toki ollut ainoa maa, jossa ostokortit olivat käytössä. Maailmansota vaikutti voimakkaasti monien muidenkin Euroopan maiden ruokatilanteeseen. Kortilla ostaminen tarkoitti, että kaikille kansalaisille jaettiin Valtion ostokortteja, joita vastaan kukin henkilö sai luvan ostaa vain tietyn määrän ruokatarvikkeita tietyllä ajanjaksolla. Ihmiset oli jaettu erilaisiin tarveluokkiin iän ja työn raskauden mukaan. Ostokortti ei silti taannut tuotteiden saatavuutta tai sitä että ruokaan oli ylipäätään riittävästi rahaa. Musta kauppa rehotti. Varsinaista suurta nälänhätää Suomessa ei tehokkaan järjestelmän ansiosta kuitenkaan jouduttu kokemaan, joskin kahvin säännöstely päättyi vasta 1954.

Leipäviljan päiväannokset tuntuvat hirmuisen pieniltä:

Lapset 12 v. asti ja kevyttä työtä tekevät 200g/vuorokaudessa

Lapset 13-16 v. ja raskaanpuoleista työtä tekevät 250g

Raskasta ruumiillista työtä tekevät 300g

Erittäin raskasta ruumiillista työtä tekevät 425g

250g of wheat flour per day is not much. Weekly portion of flour would make about 2-3 loafs of bread or about 20 rolls. Would this amount be enough for you for a week, especially if other foods would be also low?

Kahden aikuisen ja kahden lapsen perheessä leipäviljaa saattoi saada siis vain noin kilon vuorokaudessa. En tiedä tarkoittaako tuo määrä todellakin viljaa jyvinä, mutta kilosta jyviä saadaan kaiketi noin 600-700g jauhoja ja vain noin 15 g mannaryynejä (lähde). Ensimmäisen maailmansodan aikana senaatti määräsi vuonna 1918 alentamaan kotilouksien käyttämää viljamäärää seitsemään kiloon jauhoja ja ryynejä kuukaudessa henkilöä kohti, eli noin 230g päivässä. Ja erikseen henkisen työn tekijöiltä määrä alennettiin vain viiteen kiloon kuukaudessa, noin 165g vuorokaudessa. Vuonna 2012 Finravinnon tekemän tutkimuksen mukaan suomalaiset kuluttivat erilaisia viljatuotteita kuten leivät, puurot ja konditoriatuotteet, keskimäärin noin 300g vuorokaudessa. Määrät eivät tunnu lopulta ihan hirveän poikkeavilta, mutta pitää ottaa huomioon että 1900-luvun alussa suomalaisten ruokavalio perustui luultavasti paljon enemmän puuroihin ja leipään kuin nykyään. Kun samaan aikaan muustakin ruuasta oli pulaa, leivällä ei voitu paikata muun ruokavalion puutteita. Pakko myöntää että elän itse yltäkylläisyydessä. Ruoka ei koskaan ole loppu ja aina on varaa ostaa myös herkkuja. Kahvia kuluu enemmän kuin kehtaan edes tunnustaa. Ei varmaankaan tekisi pahaa hiukan vähentää syömistä, vaikka mihinkään säännöstelyyn ei olekaan tarvetta. Eikä toivottavasti tulekaan. Mutta jos tulisi, olisin luultavasti melko pulassa vaikka tykkäänkin puuroista ja marjamehuista.

Kevyttä työtä tekevän päivän ruoka-annos vuonna 1942

250g leipää

2 dl maitoa

5 g voita

14-15 g lihaa

25 g sokeria

Ruokapulaa koitettiin parhaan taidon mukaan paikata erilaisilla korvikkeilla. Säännöstelyn alkaessa kahvia sai ostaa kuukaudessa 250g yhtä aikuista kohden. Kahvin korvikkeena käytettiin mm. ohraa, perunankuorta, voikukanjuurta ja sikuria. Ensin kahvia jatkettiin lisäämällä osa korviketta, mutta lopulta kahvinvastikkeessa ei ollut lainkaan kahvia. Kortillakaan aitoa kahvia ei lopulta enää saanut, vaan myytiin pelkkää korviketta. Marjahilloja jatkettiin porkkanalla ja leipäjauhoja petulla ja jäkälällä. Pettua saatiin männyn kuoren jälsi- ja nilakerroksista. Irrotuksen jälkeen se kuivattiin, keitettiin ja paahdettiin. Pettu oli Suomessa tuttu leivänkorvike jo 1800-luvun katovuosilta. Oikein huonoina aikoina oli leivottu leipää, silkkoa, pelkästä petusta. Siitä siis sanonta, “moni kakko päältä kaunis, vaan on silkkoa sisältä”. Kurkkaa tämä Katjan video jossa hän tekee pettua ja leipoo siitä leipää. Sokeria korvattiin porkkanoista ja sokerijuurikkaista keitetyllä siirapilla. Voin vastikkeita tehtiin perunasta ja eläinten rasvasta.

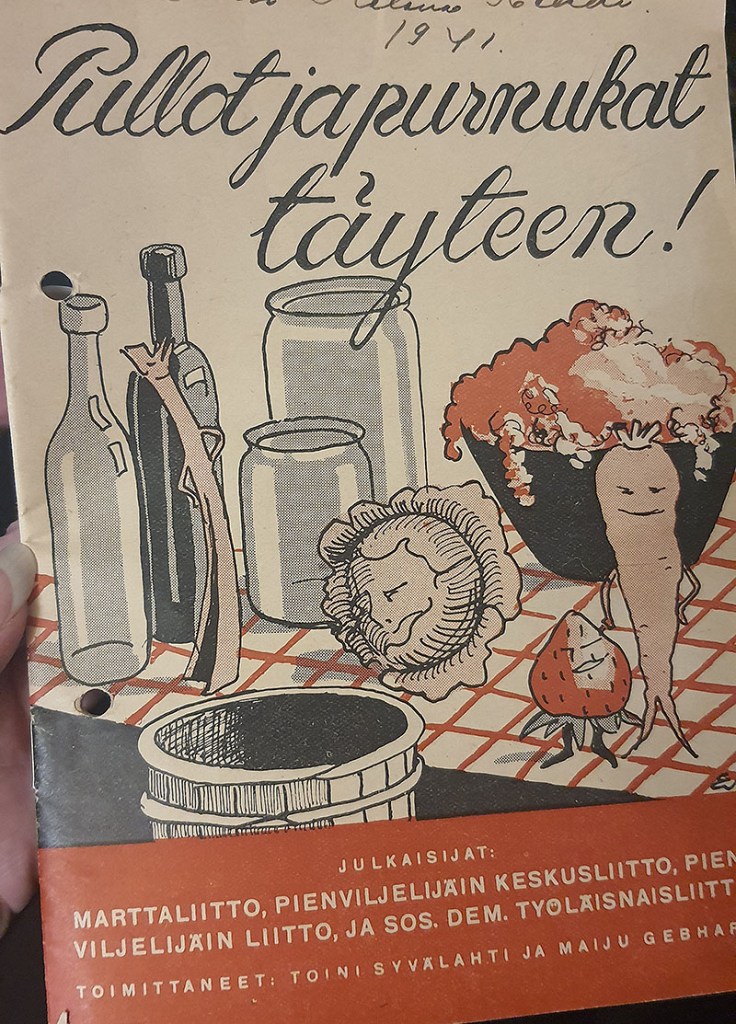

Juureksia lukuun ottamatta vihannekset eivät olleet vielä tavallisen kansan perus-ruokavaliota. Työläisväestön tärkeintä ruokaa olivat energiapitoiset ruuat. Pula-aikaan ihmisiä kannustettiin keräämään monipuolisesti luonnonantimia ja viljelemään ruokaa jopa kaupunkitalojen pienillä pihoilla. Kaupunkiasunnoissakin saatettiin kasvattaa porsaita tai kanoja. Kansanhuoltoministeriö julkaisi useita julkaisuja, joiden ohjeiden ja reseptien avulla ihmiset yrittivät lisätä ravinnon määrää ruokavaliossaan. Löysin sattumalta jokin aika sitten kirpputorilta Marttaliiton, Pienviljelijäin liittojen ja Sos.Dem. työläisnaisliiton yhteistyönä julkaiseman säilöntäoppaan vuodelta 1941. Siinä annetaan yleisohjeita säilöntään, sekä erilaisia reseptejä säilykkeisiin. Vihkonen neuvoo myös kahvin ja teen korvikkeiden valmistuksen. Vihkosen erikoisuutena ovat AIV-reseptit marjoille. Nykyisin muurahaishaposta valmistettua AIV-liuosta ei luultavasti suositella ruuan säilöntään, mutta sota-aikana se oli luultavasti paremmin saatavilla kuin sokeri. Lapsuudestani maatilalla muistan AIV-rehun väkevän ominaistuoksun eikä se kyllä eritysesti nostanut ruokahalua.

VAROITUS! Ethän käytä näitä AIV-ohjeita ruuanvalmistukseen!

Dandelion root was used as coffee substitute: pick them after rain, wash and scrape clean, chop into small pieces and dry in the oven in mild temperature. Before use, roast them in the oven so that they become golden brown but not burned. Many people seemed to think they tasted better than other coffee substitutes.

Maalla asuvilla tilanne saattoi olla parempi kuin kaupungissa, sillä heillä oli luultavasti enemmän tilaa eläimien pitoon, isot vihannestarhat, marjapensaita ja hedelmäpuita, joista saatiin satoa ja erilaisia säilykkeitä. Laki määräsi alkutuottajia luovuttamaan ylimääräisen ruokatavaran takavarikkoon, mutta tämän valvominen oli hankalaa ja usein kaupungissa asuvat sukulaiset saivatkin tuliaisia maalta ruuan muodossa. Moni maalaisisäntä ja emäntä varmasti lihotti kukkaroaan käymällä myös mustan pörssin kauppaa voilla, munilla, maidolla ja lämpimäisillä.

Jos haluat tietää millaista ruuan säännöstely oli muualla maailmalla, kurkkaa vaikkapa tämä Hannah’n YouTube-video jossa hän yrittää selviytyä viikon sota-aikaisilla ruoka-annoksilla. Oletko itse kokeillut vastaavaa haastetta? Miltä se tuntuisi?

I have been recently thinking what it would feel if we had shortage of food? How easy would it be to adjust to the fact that there are limits on how much certain foods you can buy? Would we be able to fill our bellies or would we go bed hungy? There would be no treats or sweeties, and when a bit peckish, there would not be small snacks readily available in the cupboards. We would have to settle for smaller portions, substitutional ingredients and add more berries, mushrooms and home-grown vegetables to the table.

When Finland ended up joining the WWII, first items to go under rationing were coffee and sugar, in October -39. Later or also grains and bread, tee, dried fruits, milk, cheese and butter, eggs, meat and during the worst shortages, went under the rationing. Other goods which were rationed were clothes, shoes and soap. There was also shortages of everything else, like medicine, fuel and household items. Ration cards were used also during First World War and Finland wasn’t the only country to do that. Most European countries were forced to ration their food during the war time. Buying with ration cards meant that each citizen was given National ration cards, which were valid during certain time period and gave you permission to buy certain items, only the amount the card was showing. People were divided in different groups based on age and how physically heavy work they did. Daily rations might have been quite small. Ration cards didn’t still guarantee the availability of goods or that you had enough money to buy them. Black market was blooming. Finland didn’t see actual big famine during the WWII, however coffee was rationed 15 years, untill 1954.

Daily grain portions in Finland seem very small:

Children up to 12 years and those who do very light-weight work 200g/day

Children between 13-16 years and those who do moderately heavy work 250g

People who do heavy work 300g

People who to extremely heavy work 425g

Family of two adults and two children might have been able to get only one kilo of grains per day. I’m not sure if it really means full grains, but one kilo of grains gives apparently around 600-700 g of flour and only 15 g of semolina. During First World War, senate ordered that in 1918 household amount of flours should be reduced to 7 kilos of flour and semolina per person, which is about 230g per day. And they separately determined that person doing only mental work should be reduced 5 kg per week, 165g per day. In 2012 Finravinto made study which showed that Finns are aproximately consuming grain products like bread, porridge and bakery products about 300g per day. It doesn’t seem that large difference in the amounts, but when you also consider that during the early 1900’s, Finnish diet was probably more based on porridge and bread, than these days it seems a bit more harsh. Also the fact that during the shortage, there probably wasn’t much more else to eat either, you wasn’t able to fill the void with bread. I have to admit that we live in abundance. We are never out of food and we always can afford to buy treats. We consume more coffee than I dare to admit. I don’t think it would be a bad idea to eat less, even though there is no need for rationing food. And hopefully never will. But if it would happen, I probably would be in trouble, even though I do like eating different kinds of porridges and home made berry juices.

Daily portions for those doing light-weight work in 1942 (in Finland)

250 g of bread

2 dl of milk

5 g of butter

about 14 g meat

25 g sugar

Meal portion for person doing light weight work in -42 was not big: glass of milk, just over half a loaf of French bread, small cube of butter, two thin slices of ham and under deciliter of sugar. In addition to these there was probably available some eggs, potatoes and other root vegetables, fish and berries.

People tried to mend their food shortage with substitutes. When rationing started you was allowed to buy 250g of coffee per one adult per month. People used for example oats, potato peels, dandelion roots and common chicory for substitutes for coffee. First coffee was mixed with these substitutes, but in the end there was no coffee in the substitute at all. During the worst time, people couldn’t buy any coffee even with the rationing cards, just replacement coffee. Berry jams were mixed with carrots to make larger portions, bread flour were mixed with pine tree cambium and phloem and even lichen. Cambium and phloem were collected from the trees, dried, boiled and roasted. This flour substitute was called pettu. It was well-know flour substitute in Finland already in the Great famine of 1800’s. During famine, bread was baked completely made of pettu. Bread which didn’t have any flour in it, was called silkko. We even have a proverb reminiscing the famine, loosely translated ” Many a bread look nice, but are just silkko in the middle”, meaning that things are not always what they seem. Check this video where Katja makes pine bark bread. Sugar was replaced with syrup, boiled from carrots and sugar beet. Butter substitutes were made from animal fat and potatoes.

Vegetables weren’t yet part of the Finnish people’s diets back then, except for the root vegetables. Working class preferred food with high energy-content. During rationing people were encouraged to gather lot of food from nature, like berries and wild herbs and grow their own food, even in small town yards. Some people even kept small animals in town apartments. Special ministry was appointed to take care of food shortage issues. They published guide booklets to give people instructions, recipes and tips how to make the food last. By coincidence I recently thrifted little recipe booklet published by Martha Association, Farmers unions and Sos. Dem. Women’s Workers Union in 1941. It gives general instructions how to preserve food, and has also recipes for all sorts of preserves and dried goods. Booklet also gives instructions how to make coffee and tee substitutes. Unusual recipes include AIV-preserved berries. AIV-liquid is Finnish invention. It is preservative made of formic acid and it’s used to preserve grass over the winter for farm animals. I’m pretty sure AIV-liquid is not recommended these days for human food, but during the war time it must have been more readily available than sugar. I remember the distinctive sour smell of AIV-preserved grass from my childhood in the farm, and it didn’t really raise your appetite.

WARNING! Please, don’t use these AIV recipes for preserving food.

Those who lived on the country side probably had better situation, they had more land to keep animals and grow their own food, vegetable gardens, berry bushes and fruit trees. They were able to make bigger amounts of preserves and had better supply of their own eggs, milk and butter. According to law, however, they had to give away to government produce which was over their own consumption. Regulating this was tricky and many got away with eating more than their share. Often the relatives living in towns benefitted from their country “cousins” and got little bit of extra as gifts. Many farmers probably also earned some extra pennies by selling their butter, milk, eggs and baked goodies on black market. If you want to know what rationing was outside Finland, check this Hannah’s YouTube-video where she tries war time rationing diet for a week.

Martha union with other associations published instructions to preserve food for winter in 1941.

Bottled rhubarb: clean and chop rhubarb stalks. Put the pieces into the bottles, pour rhubarb juice or water ontop untill all pieces are submerged. Close bottle.

Todella mielenkiintoinen aihe jälleen kerran! Olen katsonut Youtubesta muutamia videoita, joissa sisällöntuottajat kokeilevat pula- ja korttiajan ruokavaliota eli syövät säännöstelyn mukaisia ruoka-annoksia. Videot pistävät kyllä miettimään asiaa moneltakin kannalta. Me todella elämme yltäkylläisyydessä. Meillä (siis nykyajan länsimaisilla ihmisillä ja yhteiskunnilla) on varaa heittää ruokaa ihan vaan poiskin järkyttäviä määriä!

En ole kokeillut vastaavaa haastetta itse, mutta olen tosiaan miettinyt aihetta. Itse asiassa luin juuri Ville-Juhani Sutisen kirjan “Ruoka, valta ja nälkä 1900-luvun diktatuureissa”. Voin suositella, oli asiallinen teos, ja käsitteli paitsi suurempia poliittisia koukeroita myös ihan tavallisen ihmisen arkista selviytymistä silloin kun ruoka on vähissä.

Ihminen on todella kekseliäs olento, ja hengissä pysyäkseen tekee (ja syö) melkein mitä vain. Toivottavasti emme tosiaan joudu sellaisiin tositilanteisiin, joissa ruokaa säännösteltäisiin tai siitä tulisi oikeasti pulaa (en laske todelliseksi pulaksi sitä että leipomotyöntekijät ovat kaksi päivää lakossa ja jotakuta on harmittanut että juuri sitä omaa tuoretta suosikkileipää ei ole aamiaispöytään saatavilla vaan pitää ottaa jotakin toista merkkiä ja laatua).

Aina kun palaan tämän aihealueen pariin (ja se on yllättävän usein), minua alkaa nolottaa se miten jätän arvokasta ruokaa hyödyntämättä. Olen jo monena vuonna kasvatellut pihalla muutamia porkkanoita, ja syönyt niistä vain ne oranssit juurekset. Mutta nyt otan itseäni niskasta kiinni ja aion yrittää naattienkin hyödyntämistä!

Kommentti on nyt jo pitkä, mutta jatkan vielä sen verran että tästä(kin) asiasta eli ruoasta osaamme vain oppimamme, ja se on se mitä olemme muilta ihmisiltä itseemme imeneet. Olemme tietynlaisen ruokakulttuurin kasvatteja. Minä tutustuin aikoinaan (jumbo)herkkusieniin ensimmäisiä kertoja niin, että sienistä poistettiin jalat, sienet täytettiin ja grillattiin. En ajatellut asiaa mitenkään erityisesti, mutta tästä otin nuorena sellaisen opin että herkkusienten jalat heitetään pois. Olin kyllä nähnyt että metsäsienistä säästetään ja käytetään jalat, mutta herkkusieni oli uusi asia, ja seurasin tässä saamaani esimerkkiä. Vasta vuosia myöhemmin (kun olin jo ehtinyt heitellä haaskuuseen melkoisia määriä ihan kelvollisia syötäviä herkkusienen jalkoja) tajusin että ne jalat kannattaa myös hyödyntää. Tunsin itseni vähän tyhmäksi, mutta toisaalta se oli arvokas oivallus.

Hehkuvainen – Itseänikin harmittaa tuo että ihan liikaa tulee heitettyä pois pilaantunutta ruokaa. Siinä olisi paljon parannettavaa, sekä valmistettujen määrien tarkemmassa annostelussa, tähteiden käytössä ja säilömisessä sekä ruuan järkevämmässä ostamisessa. Yksi osasyy lienee se että asumme kauempana kaupoista ja ruokaa tulee ostettua kerralla melko isoja määriä jotta kauppaan ei tarvitse lähteä useita kertoja viikossa. Ostamme kaupoista myös hävikkiruokaa, joten se vähän kompensoi, mutta ei riittävästi. Onhan tässä melko suuri kontrasti 40-lukuun. Tätä postausta kirjoittaessani luin netissä veteraanilotan haastattelun jossa hän kertoi että rintamalla sotaväelle valmistettu ruoka oli usein todella ala-arvoista. Lihaa liotettiin tuntikausia etikassa jotta kaamea mädän haju saatiin siitä pois. Eläin oli teurastettu Satakunnassa ja sen kuljetus rintamalle kesti viikon, joten liha oli ehtinyt jo alkaa mädäntyä. Se oli kuitenkin pakko laittaa ruuaksi, sillä muuta ruokaa ei ollut. Minunkin lapsuudessani oli vielä tapana että home voitiin kuoria pois mehupullosta mehun pinnalta ja homeisestä leivästä leikattiin vain homeinen pala pois ja loppu syötiin hyvällä ruoka-halulla. Nykyisin tietämys on kehittynyt eikä homepilkkujen poistamista enää suositella vaan koko ruoka pitäisi heittää pois. Opin jo varhain että keltainen, oranssi ja musta home ovat ruokamyrkytyshomeita, valkoinen, harmaa ja vihertävä home voidaan poistaa ja ruoka olisi sen jälkeen syöntikelpoista. Itselleni tästä pois oppiminen on ollut vaikeaa, mutta kun puoliso on ruuan homeelle allerginen, ei ole ollut muuta vaihtoehtoa.

On totta että ruokatavat opitaan hyvin pitkälti muilta. Itse olen kotoa saanut kasvatuksen siihen että kaikkea pitää ainakin maistaa ja olen ollut aina melko kaikkiruokainen ja maistan mielelläni ja melko ennakkoluulottomasti uusia ruokia. Äiti oli erinomainen ruuanlaittaja ja meillä syötiin monipuolisesti paitsi lihaa ja kalaa, myös sisäelimiä ja kasviksia. Tähteet hyödynnettiin seuraavan päivän ruokiin ja usein meillä saattoikin olla esim lättyjä joiden taikinan sisään kätkeytyi eilispäivän keitetyt makaroonit. Toki uudempien ruokatuttavuuksien suhteen en ole kotoani saanut oppia, joten ne opit on pitänyt etsiä muualta; kavereilta, ravintoloista, keittokirjoista ja netistä. Kyllä sieltäkin varmasti löytyy jotain pöljyyksiä kun oikein ryhtyisin kaivelemaan, vaikka nyt yhtäkkiä ei tule mieleen oikein mitään. Ei kun hei, nythän muistankin että opin vasta muutama vuosi sitten että kukkakaalin suojalehdet voi myös syödä. Oli sekin vähän tajunnanräjäyttävä asia. Aiemmin olin aina nyhtänyt ne jo kaupassa pois (joo tiedän että niin ei saisi tehdä). Ja ihme ja kumma! Pidän keitetystä kukkakaalista, mutta höyrytetyt kukkakaalin lehdet ne vasta herkkua ovatkin! Ja sama juttu parsakaalin varren kanssa. Reilu parisenkymmentä vuotta sitten opin eräältä thaimaalaiselta että parsakaalin paksua vartta ja siinä olevia pikkuisia lehtiä ei tarvitse kokonaan heittää pois, ainoastaan se puumainen varren tyvi. Muun osan voi keittää ja siitä tulee pehmeää ja makeampaa kuin parsakaalin kukkanupuista. Sitä ennen olin käyttänyt vain ne kukkanuput.

Itse en pidä naattien pois heittämistä hirveän suurena rikkeenä. Niitä käyttäessä pitää tietää mitä voi syödä, sillä kaikki naatit eivät kelpaa ruuaksi. Esim toisen maailmansodan aikana Britanniassa ihmisiä sairastui syötyään ruokapulassa raparperin lehdistä valmistettua ruokaa. Samoin palsternakan naatit ja kukat sisältävät ihoa ärsyttäviä aineita eikä niitä pidä syödä. Itselläni kyllä naattien maku on usein luotaantyöntävä, enkä esim pidä mansikan kantojen mausta, joten yleensä jätän ne syömättä. Toisaalta taas monet puutarhan perennat soveltuvat syötäväksi, esim maksaruohot (paitsi keltamaksaruoho), kuunliljat ja päivänliljat, sekä mustaksi kuihtuneet vuorenkilven lehdet joista voi keittää teetä. Tämä on kyllä hirveän mielenkiintoinen aihe josta voisi jatkaa juttua pitkäänkin.